Navigating the IRS Landscape: Business Inventory Removed for Personal Use and Its Tax Implications

For many small business owners, the line between business and personal can often blur. It’s not uncommon, for instance, for a retail shop owner to take a product from the shelves for their own use, or a baker to bring home unsold pastries. While seemingly innocuous, the act of removing business inventory for personal consumption carries significant tax implications that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) pays close attention to. This practice, if not accounted for correctly, can lead to inaccurate financial statements, underreported income, and potential penalties during an audit.

This comprehensive guide will delve into the intricacies of accounting for business inventory removed for personal use, exploring why it matters to the IRS, how different business structures handle it, the specific IRS forms involved, and best practices for compliance.

The IRS Perspective: Why It Matters

At its core, business inventory is an asset held for sale to customers. Its cost is typically included in the calculation of "Cost of Goods Sold" (COGS) when an item is sold, which in turn reduces the business’s gross profit and taxable income. When an owner takes inventory for personal use, that item is effectively removed from the pool of goods available for sale.

From the IRS’s viewpoint, there are several key reasons why this seemingly minor act has significant tax implications:

- Accurate Income Reporting: If inventory taken for personal use is not properly removed from COGS, the business’s COGS will be overstated. An overstated COGS leads to an understated gross profit and, consequently, an understated net taxable income. The IRS wants to ensure all income is accurately reported and taxed.

- Preventing Unfair Tax Advantages: Allowing business owners to deduct the cost of goods they consume personally would essentially grant them a tax-free benefit. The tax system aims for fairness, ensuring that personal consumption is funded with after-tax dollars.

- Capital Account/Basis Adjustments: For partnerships, S-corporations, and sole proprietorships, removing inventory for personal use affects the owner’s capital account or basis in the business, which has future implications for distributions, sale of the business, or liquidation.

Therefore, proper accounting for personal use of inventory is not merely a bookkeeping detail; it’s a fundamental aspect of maintaining tax compliance and ensuring the integrity of your business’s financial records.

Accounting for Personal Use of Inventory: The Mechanics

The fundamental principle is to remove the cost of the inventory from your business expenses and recognize it as a personal draw or distribution to the owner.

1. Valuation: Cost Basis

When inventory is removed for personal use, it should generally be valued at its cost basis to the business, not its retail selling price or fair market value. The business has already incurred the cost to acquire or produce the inventory, and it is this cost that needs to be removed from the business’s deductible expenses (COGS).

For example, if a clothing boutique owner takes a shirt that cost the business $20 (and would sell for $50), the $20 cost is the amount that needs to be accounted for as a personal draw.

2. Adjusting Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

The most direct way to account for inventory taken for personal use is to adjust your COGS calculation. COGS is typically calculated as:

- Beginning Inventory + Purchases – Ending Inventory = COGS

When an item is taken for personal use, it effectively reduces the "Ending Inventory" that would have been available for sale. By reducing ending inventory, the calculated COGS for the period will be lower. Alternatively, some accounting systems might treat it as a direct reduction of "Purchases" or a separate non-sales deduction from inventory.

Regardless of the exact method, the goal is to ensure that the cost of the personally used inventory is not included in the COGS reported on your tax return.

3. Journal Entries (Conceptual)

While specific entries may vary based on accounting software, the underlying principle involves:

- Debit: Owner’s Draw / Shareholder Distribution / Partner Distribution (an equity account)

- Credit: Inventory (an asset account)

This entry reduces the inventory asset on the balance sheet and reduces the owner’s equity in the business, reflecting the personal consumption. It ensures that the cost of that inventory is not later expensed as COGS.

IRS Forms and Business Structures

The specific IRS forms and the way inventory removal is reported depend heavily on your business structure.

1. Sole Proprietorship (Schedule C, Form 1040)

For sole proprietors, inventory removed for personal use is treated as an owner’s draw. It is not an expense of the business and therefore does not appear as a separate line item on Schedule C (Form 1040), Profit or Loss From Business.

How it Impacts Schedule C:

- Part III, Cost of Goods Sold: This is where the adjustment primarily occurs. You will list your beginning inventory, purchases, and ending inventory. When you remove inventory for personal use, you effectively reduce the value of your ending inventory. This reduction in ending inventory will result in a lower calculated COGS.

-

Example: If your purchases were $10,000, beginning inventory $2,000, and ending inventory (before personal use) would be $3,000. If you take $500 worth of inventory for personal use, your true ending inventory is $2,500.

- COGS (without adjustment): $2,000 + $10,000 – $3,000 = $9,000

- COGS (with adjustment): $2,000 + $10,000 – $2,500 = $9,500

- Wait, this is wrong. If ending inventory is reduced by personal use, then COGS will increase by that amount. This is the opposite of what we want.

Correction/Clarification: The goal is to prevent the cost of the personally used inventory from being expensed.

- Method 1 (Adjust Purchases): Some systems might treat the personal use as a reduction in "Purchases" when calculating COGS. So, if you bought $10,000 of inventory and took $500 for personal use, your "Purchases" for COGS calculation would be $9,500. This directly reduces the amount that would flow into COGS.

- Method 2 (Adjust Ending Inventory – Most Common and Simplest): If you take inventory for personal use, that inventory is no longer part of the business’s ending inventory. By removing it from the ending inventory count, the calculated COGS will be higher, which correctly reflects that less inventory was left for sale.

- Example: Beginning Inventory $2,000 + Purchases $10,000 – Ending Inventory $3,000 = COGS $9,000.

- If $500 of inventory was taken for personal use, and this was not removed from "Purchases," then the ending inventory for business sales purposes should be $3,000 – $500 = $2,500.

- So, COGS becomes $2,000 + $10,000 – $2,500 = $9,500.

- This increase in COGS by $500 is incorrect if the goal is to prevent the deduction.

Re-Correction: The correct approach is to prevent the cost from being deducted as COGS.

- The most straightforward way is to reduce the "Cost of Goods Sold" amount by the cost of the inventory taken for personal use.

- In accounting, this is often done by debiting an owner’s draw account and crediting an inventory asset account. When preparing Schedule C, the actual cost of goods sold is reduced by the value of inventory taken for personal use.

- Alternatively, on Schedule C, Part III, line 36 (Cost of Goods Sold), you would adjust your purchases or ending inventory to reflect that the personally used inventory did not contribute to goods sold. Many simply add the cost of inventory taken for personal use back to their gross income (Line 7) or reduce the COGS calculation directly.

- A common practice is to treat the cost of inventory removed for personal use as a reduction in "purchases" when calculating COGS, or to make a specific adjustment within the COGS section (e.g., as part of "Other costs" or a direct reduction of total COGS).

- Simpler explanation: The net effect must be that the cost of the personally used item does not reduce your taxable profit. If your accounting system calculates COGS based on all inventory, you must then add back the cost of personal use inventory to your net profit, or reduce your COGS by that amount. This results in higher taxable income.

2. Partnership / Multi-Member LLC (Form 1065, K-1)

For partnerships and multi-member LLCs (taxed as partnerships), inventory removed for personal use by a partner is treated as a partner distribution.

How it Impacts Forms 1065 and K-1:

- Form 1065, U.S. Return of Partnership Income: The partnership’s overall COGS would be adjusted on Form 1065, similar to a sole proprietorship, to prevent the cost of the distributed inventory from reducing the partnership’s taxable income. This ensures that the partnership’s ordinary business income (or loss) reported on line 22 is accurate.

- Schedule K-1 (Form 1065), Partner’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc.: The value of the inventory taken for personal use (at cost) is reported as a non-cash distribution on the partner’s Schedule K-1, typically in Box 19, "Distributions," code A (Cash and marketable securities) or a similar code indicating a non-cash distribution. This distribution reduces the partner’s capital account and their basis in the partnership.

- Basis Impact: While generally not immediately taxable, distributions reduce a partner’s basis. If distributions exceed a partner’s basis, the excess can become a taxable capital gain.

3. S Corporation (Form 1120-S, K-1)

For S corporations, inventory removed for personal use by a shareholder is treated as a shareholder distribution. The rules here can be a bit more complex due to basis limitations and accumulated adjustments account (AAA).

How it Impacts Forms 1120-S and K-1:

- Form 1120-S, U.S. Income Tax Return for an S Corporation: Similar to partnerships, the S-corp’s COGS calculation on Form 1120-S must be adjusted to exclude the cost of inventory taken for personal use, ensuring accurate ordinary business income (or loss) reported on line 21.

- Schedule K-1 (Form 1120-S), Shareholder’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc.: The cost of the inventory is reported as a non-cash distribution to the shareholder. This is typically found in Box 16, "Distributions," code D (Cash and marketable securities) or a similar code.

- Basis and AAA Impact: Distributions from an S-corp first reduce the shareholder’s Accumulated Adjustments Account (AAA), then the shareholder’s basis. If distributions exceed basis, the excess can be taxable as a capital gain. If the S-corp has accumulated earnings and profits (E&P) from prior C-corp years, distributions exceeding AAA and basis can be taxed as dividends.

- Potential Deemed Sale: In some cases, if the fair market value (FMV) of the inventory at the time of distribution exceeds its cost basis, the S-corporation might be required to recognize a gain as if it had sold the inventory at FMV. However, for typical inventory items, the cost basis approach is generally used for personal use removals. It’s crucial to consult a tax professional for complex S-corp distributions.

4. C Corporation (Form 1120)

C corporations are separate legal and tax entities from their owners. When a C-corp owner takes inventory for personal use, it’s generally not treated as a simple owner’s draw.

How it Impacts Form 1120:

- Employee Compensation/Fringe Benefit: If the inventory is taken by an employee-shareholder, it might be considered additional compensation or a fringe benefit. If treated as compensation, it’s taxable to the employee, and the corporation can deduct the cost (or FMV, depending on the specific fringe benefit rules) as an expense. It would be reported on the employee’s Form W-2.

- Dividend Distribution: Alternatively, it could be treated as a non-cash dividend distribution. In this case, the corporation does not get a deduction for the distribution, and the shareholder is taxed on the fair market value of the inventory as a dividend (reported on Form 1099-DIV).

- Deemed Sale: If the C-corporation distributes inventory with a fair market value greater than its basis, the corporation generally recognizes a gain on the distribution as if it had sold the property for its fair market value. The shareholder then receives a dividend equal to the FMV. This results in double taxation: once at the corporate level (on the gain) and once at the shareholder level (on the dividend).

- COGS Adjustment: Regardless of the characterization, the C-corp’s COGS must be adjusted on Form 1120, U.S. Corporation Income Tax Return, to ensure that the cost of the personally used inventory does not reduce the corporation’s taxable income, unless it’s properly expensed as compensation.

Due to the potential for double taxation and complex rules, C-corporation owners must be particularly careful and consult with a tax advisor when taking inventory for personal use.

Best Practices for Compliance

To avoid IRS scrutiny and ensure accurate tax reporting, business owners should adopt the following best practices:

-

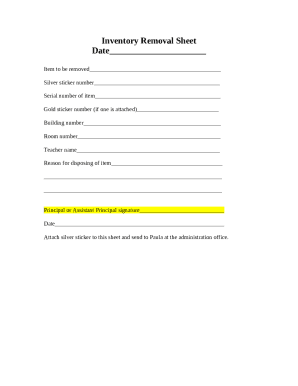

Maintain Meticulous Records: Keep a detailed log of all inventory removed for personal use. This log should include:

- Date of removal

- Description of the item(s)

- Quantity

- Cost basis of the item(s)

- Reason for removal (e.g., "owner’s personal use")

- Name of the owner/partner/shareholder who took the item

-

Implement a Clear Policy: Establish a formal policy for how inventory removed for personal use will be handled, communicated to all relevant parties (owners, partners, employees).

-

Regularly Review and Reconcile: Periodically review your inventory records and reconcile them with your accounting entries. Ensure that all personal use inventory has been properly adjusted out of COGS and recorded as an owner’s draw or distribution.

-

Consult a Tax Professional: The rules surrounding inventory and distributions can be complex, especially for partnerships and corporations. A qualified CPA or tax advisor can help you understand the specific requirements for your business structure and ensure you are in full compliance with IRS regulations. They can also assist with proper valuation and journal entries.

-

Avoid Commingling: While convenient, habitually taking inventory without proper accounting blurs the lines between business and personal expenses. Maintaining strict separation is always the best approach. If an item is taken, immediately record it.

Conclusion

Removing business inventory for personal use is a common occurrence, but it’s far from a tax-exempt perk. The IRS views inventory as a business asset intended for income generation, and its diversion for personal consumption must be properly accounted for to prevent the understatement of taxable income.

Understanding the specific requirements for your business structure – whether a sole proprietorship using Schedule C, a partnership or LLC using Form 1065, an S-corporation using Form 1120-S, or a C-corporation using Form 1120 – is crucial. By accurately valuing the inventory at its cost basis, properly adjusting Cost of Goods Sold, and meticulously documenting each instance, business owners can navigate the IRS landscape confidently. Remember, transparency and diligent record-keeping are your best allies in maintaining tax compliance and avoiding costly penalties. When in doubt, always seek the guidance of a tax professional.